by Michaela Söllinger, IFOR Austria

(This article was also published with minor changes in the Austrian magazine Spinnrad, Vol. 4 (2019))

Picture 1: Sunset over Guaviare harbor

Picture 2: Fishing pond in main hamlet of San José de León

How does reconciliation happen? How does a community begin to build a story of peace? How do ex-combatants reconnect with their communities, when it is these same communities that have suffered from the conflict?

During a recent trip to Colombia (July to October 2019) I was able to witness active reconciliation work, even if only for a short moment. Despite many shortcomings and problems with the 2016 Peace Accords between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP (then the largest and oldest guerrilla group in Latin America), many initiatives to promote reconciliation between communities and individuals are currently being carried out in Colombia. In order to gain better insight, I chose two specific activities–the word and textile work–to better understand how communities and individuals are engaging in the process of post-conflict reconciliation.

San José de Guaviare – Tukanos Orientales

Picture 3: Fishing in Guaviare

Guaviare is a department in the southeast of Colombia that is sparsely populated by indigenous peoples, small-scale farmers and some large-scale landowners. A newly paved road between various shades of green leads to San José de Guaviare. The capital of Guaviare is located in the middle of a savannah alongside the River Guaviare, named in accordance with it’s capital city. Upon closer inspection, the shades of green mostly turn out to be large-scale cattle pastures or newly planted oil palm plantations. Original steppe grass, the famous water reservoirs of the savannah with their moriche palms and the receeding Amazon rainforest can be seen on the wide horizon. On the outskirts of San José de Guaviare is the Panuré Indigenous Reserve, where several indigenous communities of the Tukanos Orientales met for the first “Intercultural Peace and Reconciliation Meeting between ex-FARC fighters and the Tukanos Orientales Reserves of the Department of Guaviare”.

So, who are the Tukanos Orientales? Marcelo, an indigenous teacher, explained their history to me with the drawing below, which was also on the drinking bowl that we received for the occasion.

Picture 4: Drinking bowl

“This is a rock drawing from the Vaupés Department (Amazonia, which shares a border with Brazil) from the village of Piedra Ñi, and means black stone. It is in this place, where the equator crosses the rock, that our grandparents considered the center of the world. There, the creators of the universe made this drawing, which represents all the peoples of the Tukanos Orientales: the celestial people, the earth people, the aquatic people, the anaconda and stone people. It embodies the frogman and the guacamayo birdman. If you look at the drawing from one side, you can see a head and a torso. If you turn the drawing, you can see the person in the middle of the world. These are the Tukanos Orientales.”

During the event, around 200 indigenous people from the Panuré, Itilla, El Refugio, La Fuga and Asunción reserves met for the first time with around 50 recently demobilized FARC members from the surrounding reintegration areas of Las Charras and Las Colinas, a newly-settled area where demobilized guerrilla fighters lived together after the peace agreement was signed. In the Panuré’s Community Center, Gabriel Muyuy, UN High Commissioner advisor on ethnic issues in Colombia, initiated a public conversation defined as, “Getting to Know Each Other, Acknowledgement and First Agreements”. Gabriel is indigenous to the Inga people who, like the Tukanos Orientales, have their origins in the Amazon region. His work to advocate for greater indigenous participation in regional, national and international politics has granted him deep respect throughout the region, enabling him to create an atmosphere of trust. The event began with a spiritual event the day prior, with 250 participants. On the first day of the talks, a dried fruit bowl with mambé – roasted, crushed coca leaves – made rounds, while participants began to get to know each other through group storytelling.

Getting to know each other: Several demobilized FARC members stepped, one by one, into the middle of the meeting house to share parts of their story with the audience: How and why they had left their community and their territory, what they experienced during their time as FARC members, and encounters with their own people, even their own community or family, during this time. In response, leaders from the indigenous reserves shared how they experienced the conflict as civilians and the challenges they are currently facing (apart from social conflicts, there are still several armed groups active in the region).

In addition, basic rights that are shared by all indigenous people (both ex-combatants as well as civilians) were refreshed in a joint ceremony. While indigenous rights encompass three areas–autonomy, territory and cultural identity–the Colombian state often does not fulfill them. Both ex-combatants and civilians alike expressed their concern over the lack of compliancy regarding territorial rights. Several reserves have been waiting for their territories to expand for many years due to a lack of space. The problem is complex, and even more complicated due to the semi-nomadic nature of the Tukanos Orientales peoples. Do reserves make sense for semi-nomaid people? Does the right to autonomy in a specified territory?

As the event went on, it became evident that participants primarily wanted to define their indigenous identity by ideas of conscience, self-image and belonging, and expressed a desire to accept and strengthen this identity.

Recognition: After careful listening and reflection, all the participants seemed to have reached a consensus about the need to use the different life experiences to face the challenges of the Tukanos Orientales together. Before the participants euphorically moved on to the next step, Gabriel Muyuy sounded a note of caution and a reminder to include and recognize the knowledge of previous generations. He explained that one of these insights, which he had always dismissed as meaningless as a teenager, is summarized in one of his people’s guiding principles as: “As long as we live, we should think carefully in order to live well (Mientras vivamos, pensamos bien para vivir bien).” He invited those present to recall the principles of their own ancestors and warned of overzealous agreements and promises.

Picture 5: Group discussions in the community house

Agreement: After a night of celebration and Walking, a traditional dance of the Tukanos Orientales, the participants were invited to share their findings and to name topics that they would like to work on together with everyone. The day started with a proposal that was met with the greatest approval. The proposal suggested finding a new way to refer to ex-combatant fighters. “We don’t want to call them ex-fighters anymore; we now see them as something different.”

The day concluded with an agreement to set up a committee, which includes both representatives from the reservations as well as demobilized FARC fighters, and which would commit to finding a new way to refer to indigenous ex-combatants.

San José de León, Antioquia – Small scale farmers

Picture 6: Main hamlet of San José de León

San José de León is embedded on green hills only about five kilometers away from the Ruta del Sol (a highway project running between Medellin and Turbo, currently under construction) and which will ultimately connect inland Colombia to it’s Caribbean ports.

At the opening of the exhibition “(Des)tejiendo Miradas” (in English, [Un]weaving views) San José de León presented itself as a vivid, emerging rural zone which, only two years prior, became home to approximately one hundred demobilized guerrilla fighters, some of them with families. At the end of October 2017, the former guerrilla fighters left the reintegration area they had been assigned to, due to the lack of productive projects that could lead to independent and sustainable livelihoods. They came and built homes in the area which would later become San José de León. Before this, there were approximately 500 families living on farms scattered throughout the countryside, with a small school on the edge of a river. Today, San José de León has become a busy village with a lively community life and is considered one of the most successful integration projects to emerge after the 2016 peace agreements.

The road leading into the hamlet arrives at the meeting house, where we eagerly awaited the opening words of the exhibition.

Picture 7: The exhibition hall

The exhibition was installed in a wooden house where local community members gathered before the opening.

Rubén, a local political leader representing the newest residents (demobilized FARC fighters and their families) opened the exhibition with a speech, emphasizing the importance of working together with the original residental population. Rubén went on to state that when demobilized guerrilla fighters first arrived, they received warm welcome from the original residents. They did not allow themselves to be intimidated or influenced by rumors from outside, and instead continuously supported the former FARC fighters in their plans to rebuild a civilian life. Rubén is convinced that a prospect for a long-term civil life would not have been possible for the demobilized FARC without this initial support and participation from the original residents.

Other demobilized residents also talked about the many times they had been tempted to give up their new ways of life. The open arms and the acceptance that the original residents of San José de Leon had always showed them significantly contributed to their ability to persevere and actively commitment to peace.

This warm reception has been reciprocated by the ex-combatants, as Maribel, president of the council of original residents, emphasized in her speech. This reciprocity allowed the entire population to benefit from international programs and projects which arose after the peace treaties, in a region which has long suffered from the presence of armed groups and a chronic absence of social services, like health and education. Hence, the river that connects the old school with the new hamlet is now part of a new joint ecotourism project and the freshly trained nature guides, including Maribel, are waiting for the first visitors.

Maribel was also able to take part in the “(Des) tejiendo Miradas” project. In cooperation with various national and international universities, individual memories were discussed and illustrated with the help of textile works. For Maribel, old stories were unwoven and new ones woven. She says, “The next story we write will no longer be about an era of violence, but we will tell how we weave a new fabric (also understood as social fabric), with our hands, how we will have built a new history of this rural area. This also includes the trust that will we have built between the long-established, who were born here and the new members of the community.”

A former guerrilla fellow described the one-year process of creating the textile pieces as follows, ‘When I went to the workshop, I thought we would learn textile work, that is, the technology. Now I know that it was not so much about learning to weave, knit or sew, but that they had another goal in mind, which is now very important to me. Through weaving we can express our own story, events we suffered from, what we saw with our own eyes, what each of us felt. So I learned something new every day, and you can see that in the work.’

Others said that working with textiles allowed them to take a breath, to get–at least for a moment–rid of their frustrations and their worries, something they often can’t find the right words for. In this sense, the participants and artists encouraged us to interpret the pictures ourselves and let the textiles tell the stories.

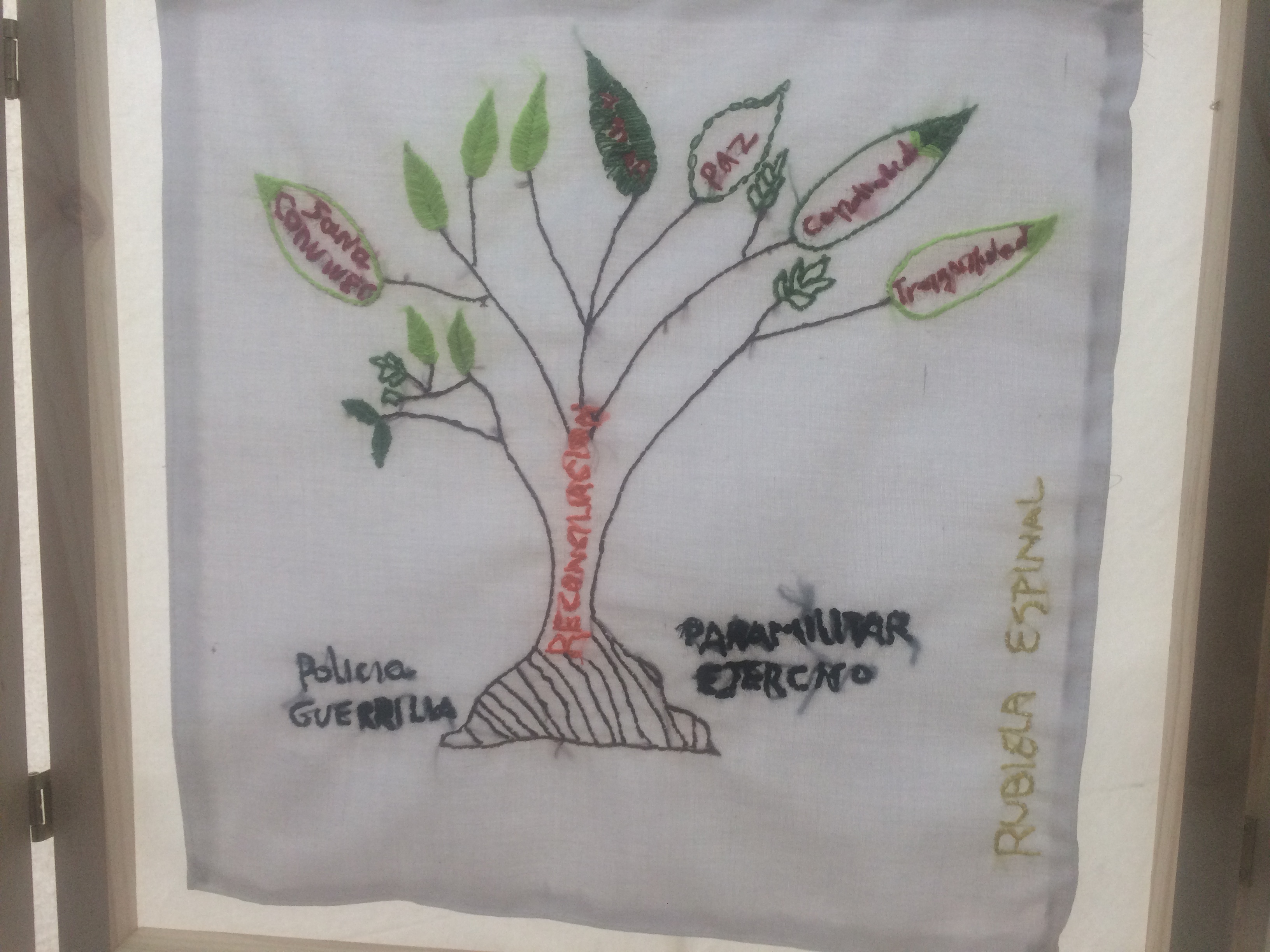

Finally, we could access the exhibition. In the wooden house there were various framed pictures on the walls, arranged according to subject groups such as reconciliation or uncertainties (see pictures).

Picture 8: Reconciliation

Picture 9: Reconciliation tree

Picture 10: Uncertainties

In the middle of the room, photographs printed on textiles, with stitched silhouettes showed most important stages of the past three years in the history of the ex-fighters; starting from the jungle camps, through the demobilization areas, to their lives in San José de León.

At this point I followed the instructions of the artists: The pictures should speak for themselves, the stories are in the pictures, and what the viewer sees.