Para la versión en español, haz clic aquí.

Written by Pendle Marshall-Hallmark, FOR Peace Presence accompanier, 2/17/2017

The day I arrived in Colombia to begin my new position as an international human rights accompanier, the decaying, mangled bodies of Afro-Colombian community activist Emilsen Manyoma Mosquera and her partner Joe Javier Rodallega were found on the outskirts of their Buenaventura neighborhood. A few days prior, the couple had been kidnapped by a group of people allegedly pertaining to one of the strongest neo-paramilitary drug-trafficking groups in the country, called “Los Urabeños“.

Emilsen Manyoma Mosquera, prominent human rights activist in Buenaventura, was kidnapped and then killed.

Emilsen, a prominent leader of the victim’s advocacy organization CONPAZ, and whom FOR Peace Presence had accompanied on several occasions, was an outspoken critic of paramilitary drug trafficking and governmental corruption in the region. She had publicly denounced the link between business expansion near the port of Buenaventura, and the rise of drug-trafficking and neo-paramilitary presence.

The couple’s death was reported internationally, but it was by no means shocking. The total number of human rights defenders that were killed in Colombia last year remains a hot subject of debate, but according to the advocacy group Front Line Defenders, Colombia made up for over 30% of all killings worldwide. In spite of the fact that Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize last year for his efforts to broker a peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC (the country’s largest and oldest left-wing guerrilla group), the number of death threats and killings of human rights defenders continues to increase.

The reason for such an increase in violence is complex, but is unequivocally (and ironically) linked to the peace process. Complying with the agreement, the FARC is only just now beginning to relinquish its control over large swaths of the country. As it retreats, new armed groups like Los Urabeños (most of which are right-wing affiliated and drug-profit motivated) are clamoring to take its place.

I just returned from an accompaniment trip to Buenaventura with two other coworkers from the Fellowship of Reconciliation Peace Presence, the Bogotá-based international human rights organization I am a part of. FORPP aims to give greater visibility to the struggle for human rights in Colombia by providing both physical and political accompaniment to human rights defenders in the country.

For this trip, my coworkers and I had been called to accompany the Interchurch Commission of Justice and Peace (ICJP) in its efforts to support the work of community activists living in what they´ve dubbed “Humanitarian Spaces”: neighborhoods that have declared themselves neutral, violent-free zones in what is otherwise an incredibly unstable city.

According to a 2015 Human Rights Watch report, Buenaventura had one of the highest rates of forced displacement in Colombia. The vast majority of the inhabitants of these Humanitarian Spaces are displaced peoples who originate from the Afro-Colombian communities along the nearby Río Naya and Río Calima, primary drug-trafficking routes for any groups interested in transporting product from the interior of the country to the Pacific’s international market.

In fact, Emilsen Manyona was herself originally from an Afro-Colombian community located on the Río Calima. According to Colombia’s 1993 “Ley 70” (70th Law), all communities officially recognized as Afro-Colombian are entitled to certain autonomy and land rights. In March of 2016, FORPP attended a celebration of the official recognition (and thereby legal empowerment) of all Afro-Colombian communities located along the Río Naya.

For a number of years, Buenaventura’s casas de pique (“chop houses”, ocean side huts infamous for being the sites of human dismemberment carried out by rival armed groups) haunted resident in the areas of the city most susceptible to business development interests. In Wards 1 through 4, where a boardwalk is currently slated for construction as part of the city’s newest efforts to boost tourism to the area, there has been a long struggle on the part of residents to gain official status as a Humanitarian Space, area entitled to certain protections by the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, and thereby from the Colombian government. At the time of this writing, one street in particular (Puente Nayero) is receiving constant military presence at its entrance gate.

My coworkers and I had originally planned to accompany the ICJP in its preparations to carry out an event celebrating the inauguration of the cultural center in the Humanitarian Space at Puente Nayero, but our agenda was quickly changed just before our arrival.

On the night of February 10th, members of another community that the ICJP supports–the indigenous Wounaan Nonam people of the Santa Rosa de Guayacán Reservation on the Río Calima, just east of Buenaventura–were deeply disturbed by the sounds of motorboats and strangers passing through their village. The villagers were certain that these boats belonged to the armed actors who had one week previously kidnapped and brutally beaten a man from their community.

Since January 26th, they had been physically confined to their homes by these individuals, unable to leave the immediate area to tend to their crops further inland. Quickly running out of food and afraid for their lives, they decided to leave everything behind and flee to the city on February 11th. It was the second time the community had been displaced–in 2010, under similar circumstances, they were forced to refuge in Buenaventura for over a year.

After an all night bus ride from Bogotá, my coworkers and I walked from the terminal to Buenaventura’s City Hall, where we encountered the ICJP with a little over 30 members of the displaced Wounaan Nonam community. The group was waiting for some kind of response from the local government, but the fact that it was a Saturday made this improbable. They looked exhausted, and had no food or water to speak of. There were mothers lying partially naked on the concrete steps, some breastfeeding their children as passersby muttered disdainfully under their breath. A man who was apparently from a local news channel began to take photos and video recordings of the group.

After waiting for several hours, a decision was made to migrate from the steps of City Hall to the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría), where the group could escape the spotlight. Many barefoot, the community members walked through the streets of downtown Buenaventura holding the few belongings they had brought and ignoring the stares from the surrounding crowds. The Governor of the Reservation and the ICJP were eventually able to work out a plan with the city that would enable the villagers to stay a few nights in the Buenaventura Children’s Center, an after-school vicinity with dysfunctional plumbing and a handful of disheveled, half-empty classrooms near the city’s main hospital.

We spent the second day of our accompaniment at the Children’s Center with the Santa Rosa de Guayacán community as they struggled to get organized. The remaining members arrived that evening from the Río Calima, leaving the village completely and officially deserted. Improvising a makeshift wood-fired grill in the corner of a concrete soccer pitch, the community took almost all day to make a meal large enough to feed everyone (by that point 141 people): a humble but delicious mixture of rice and fish soup.

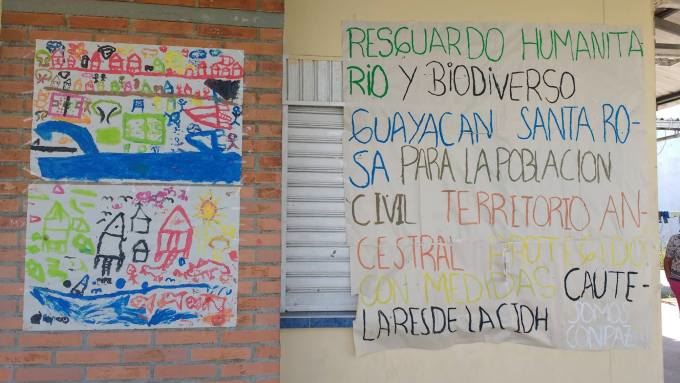

Children occupied themselves by painting a series of images of their village, but the Governor expressed concern over the amount of valuable school time that they were missing. He also pointed out that the lack of space in the Buenaventura Children’s Center was impeding the community’s ability to carry out important cultural practices at the frequency they were accustomed to, or to treat their ill with traditional healing methods. He was worried about how people would adjust to such a makeshift home.

Children of the Santa Rosa de Guayacán Humanitarian Reservation community paint a poster with images of their homes on the River Calima.

In a meeting with regional police forces on Monday, the Reservation’s Governor and Women’s Committee Coordinator recounted the trauma of their displacement. “We are being forced both physically and psychologically from our land,” the Governor said, “We are going to keep fighting for our existence.” The two leaders explained that villagers had left behind pets, livestock, and valuable solar panelling. Armed only with wooden batons, the “Indigenous Guard” of the community, though it had maintained constant 24-hour vigilance of the property ever since the aforementioned kidnapping, was powerless in the face of gunmen. Swallowing their pride, all but five adults (who stayed to wait for further transport with around 30 children) had immediately fled to Buenaventura.

Face to face with high ranking police officers, the Women’s Committee Coordinator emphasized the importance of state-sponsored public safety, and denounced the lack of adequate military and police vigilance on the Río Calima. “The government says there are no armed actors on the river,” she said, fierceness in her voice, “But there are. We have seen them.” The Governor asserted that the territory’s guerrilla groups have now been replaced by neo-paramilitaries.

Posters painted by children are hung at the entrance to the Buenaventura Children’s Center. The one on the right reads, in English: “Biodiverse Humanitarian Reservation for the Civilian Population of Santa Rosa de Guayacán; Ancestral territory protected by precautionary measures of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. We are CONPAZ.”

By our final day of accompaniment, several local and international humanitarian aid organizations (including Doctors Without Borders, the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees, and the International Committee of the Red Cross) had appeared on sight. The Santa Rosa de Guayacán indigenous community continues to inhabit the Buenaventura Children’s Center in a state of crisis. At the time of this writing, no arrests have been made in relation to their forced displacement.